First published 23/7/25; Updated 25/7/25

New evidence, the “Ket-Mid study”, has been released providing some support for the use of ketamine as a treatment for status epilepticus.

The rationale for the trial is well summarised in the opening paragraph:

- “Current guidelines recommend benzodiazepines (BDZs) as the initial anti- seizure medication (ASM) for GCSE, but up to 40% of patients are resistant to first-line BDZ therapy. Additionally, about half of BDZ-refractory GCSE are not aborted by second-line ASMs, such as levetiracetam, valproate, and phenytoin. As GCSE continues for a longer duration, it becomes more resistant to control and is associated with progressive brain damage and increased risk of death, chronic epilepsy, and long-lasting neurocognitive deficits. Accordingly, early termination of GCSE is crucial for improving clinical outcomes as “time is brain.”

This article will provide the following:

- Brief summary of the Study Details

- Assessment of the Prior Probability that ketamine provides benefit in terminating status epilepticus.

- Summary of the Results of the study

- Critique of the study highlighting issues that affect its generalisability

- Whether Practice Change is warranted as a result of this study

- How to incorporate practice change within the Status Epilpeticus Treatment Algorithm

- Practical Tips for dosing and drug delivery of ketamine when treating status epilepticus

- This was a double blind, randomised controlled trial (RCT), evaluating the efficacy of ketamine to terminate seizures in children (aged 6 months to 16 years old) presenting with generalized convulsive status epilepticus (GCSE)

- Small study of 144 patients enrolled in Egypt

- Interventions:

- Control arm: IV Midazolam 0.2mg/kg + Placebo

- Treatment arm: IV Midazolam 0.2mg/kg + Ketamine 2mg/kg (max 60mg)

- Both midazolam and ketamine/placebo were infused over 2 minutes

The prior probability (pre-study or “pre-test” probability) that ketamine added to midazolam would improve efficacy in terminating seizures:

- Significant observational evidence through case series/reports of benefit and an observational before-and-after retrospective study showing benefit.

- Animal studies showing ketamine “works synergistically with BDZs in not only terminating seizures but also mitigating neuronal damage”.

- Mechanism of action of ketamine:

- “Unlike BDZs that work as allosteric agonist for g-aminobutyric acid (GABA)A receptors, ketamine is a noncompetitive glutamate antagonist acting on N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptors. “Ongoing seizure activity is associated with rapidly progressive downregulation of inhibitory GABAA receptors and upregulation of excitatory NMDA receptors, rendering prolonged seizures more resistant to GABAergic agents but remaining responsive to NMDA antagonists. Therefore, using ketamine in conjunction with BDZs represents a rational combination to target both enhanced NMDA-mediated neuroexcitation and remaining functionally active GABAA receptors”

- The history of evidence based medicine, suggests we should generally assign a low prior probability of benefit (e.g. in the region of 10%) when evaluating either a new drug or an old drug for a new indication (like ketamine for GCSE). However, with the above prior evidence the prior probability is likely substantially better than this.

- Huge benefit seen in the primary outcome: seizure cessation at 5 minutes was 76% in the ketamine group versus 21% in the placebo group.

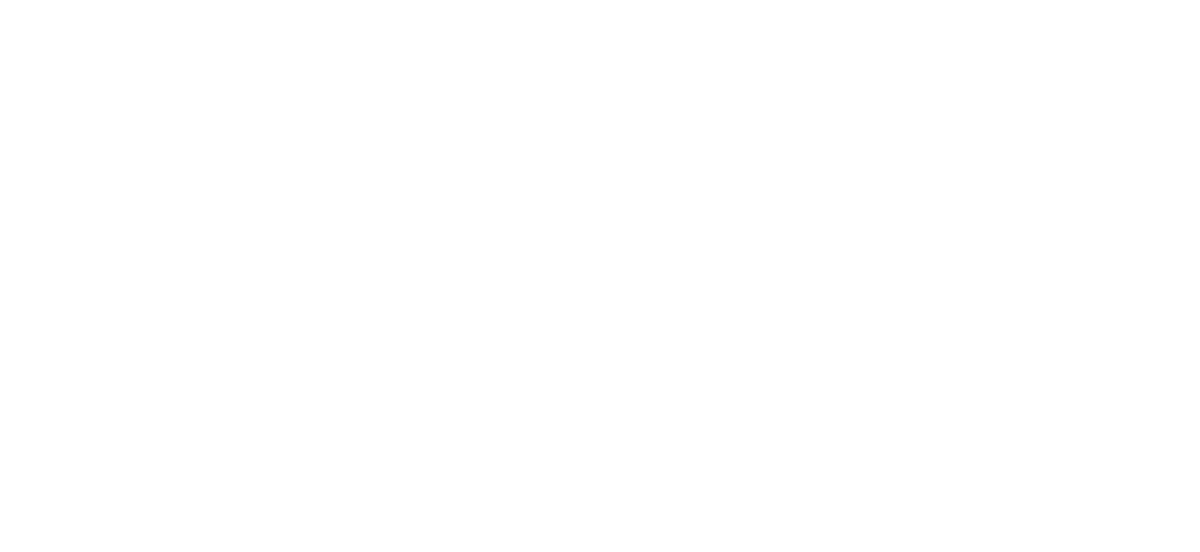

- Also clear benefits in secondary outcomes such as seizure cessation at further timepoints (15 min, 35 min and to a lesser extent 55 min) and large reduction in intubation (4% versus 21%).

- See study table 2 below.

- Small study = 144 patients at a single hospital.

- Low resource country – Egypt – with seemingly low resourced pre-hospital services as patients had an average of 34 minutes from seizure onset to hospital arrival and none of the patients received any benzodiazepines pre-hospital before enrolment in the study.

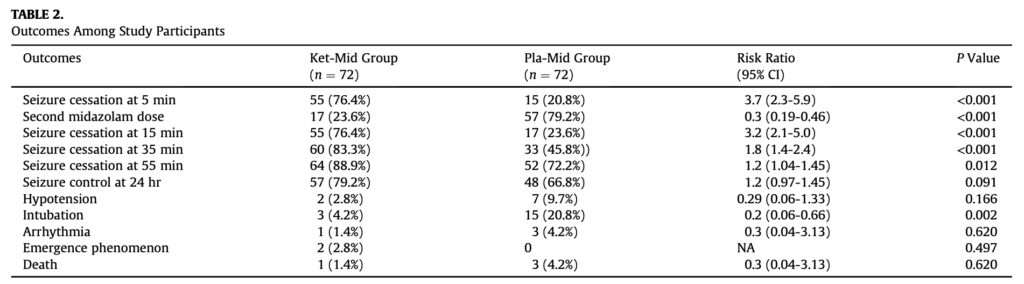

- Very low rate of success of BDZs, 21% response rate to midazolam at 5 min only increasing to 24% after the 2nd midazolam dose. This is far lower than our clinical experience and observational data. It is well described that BDZs have substantially reduced effectiveness when delivered > 15minutes after seizure onset (for reasons explained in the prior probability section above). The very long duration in this study (average of 34 min) before patients received their first medication probably explains this. Consequently, the magnitude of combined ketamine/midazolam benefit over midazolam alone is likely exaggerated by this effective straw-man comparison and this affects the generalisability of these findings to high resourced countries where midazolam would be given much earlier, often pre-hospital. Indeed study table 3 below shows that in patients who presented <30 min (about 40% of the patients) the relative benefit of the addition of ketamine was substantially reduced as midazolam alone was relatively more effective than when given later – however there was still a 40% benefit of adjuvant ketamine (compared to a 67% benefit in patients presenting >30min). With this group who presented within 30 minutes, in the likely few patients presenting early (<15min) I suspect the efficacy gap between the medications would be much smaller or indeed, non-existent (data not provided).

- Therefore, this study is more generalisable to patients presenting early with “intractable status epilepticus” that has failed to respond to BDZs or patients presenting late who have not yet received any treatment. By contrast, while informative, it is not particularly generalisable to the early treatment of status epilepticus.

- Termination of seizure was based on clinical observation not EEG, which is very much real-world practice in most EDs, however this does not preclude the small possibility that ketamine resolved convulsions but may not have resolved non-convulsive status epilepticus (to any greater extent than can occur with midazolam alone).

- Risk of bias

- The afore mentioned methodological issues constitute “visible bias” that likely bias towards ketamine benefit.

- “Invisible bias” remains as always, due to factors such as publication bias (e.g. negative studies are far less likely to be published or even submitted for publishing).

- This small single RCT demonstrated a truly dramatic benefit.

- The combination of prior probability and these study results, discounted for the risk of bias, suggest at least a moderate probability that ketamine is efficacious in terminating status epilepticus in combination with midazolam in patients who present late or who have intractable seizures resistant to midazolam. However, to have high confidence in the findings we need to see replication of the study.

- When deciding on whether to change practice, one must consider the real-world costs and benefits of change (e.g. medical, financial, practical and time), while awaiting replication of this study finding (which could take years).

- Time is brain in status epilepticus and as ED clinicians we must act to terminate seizures as early as possible to prevent permanent neurological disability in the most rational and safe approach, based on the available evidence. To achieve this, I believe ketamine must now be considered as part of this approach.

- Ketamine is incredibly cheap, we have high familiarity with it and used appropriately by trained ED clinicians, is extremely safe; indeed, much safer than sedating agents typically used in the status epilepticus algorithm such as midazolam and general anaesthetics such as propofol. In fact, the totality of the available evidence now demonstrates ketamine to be a more effective and safer agent for the treatment of status epilepticus than propofol. Therefore, arguably based on this study, ketamine should, at the very least, be used prior to consideration of using propofol and intubating a patient with intractable GCSE. The moderate probability of ketamine achieving seizure termination and preventing all the harms associated with intubation and ventilation cannot reasonably be ignored and I personally could not countenance using propofol before trialling ketamine anymore.

- In contrast, there is insufficient evidence to suggest ketamine should be used instead of midazolam as the first drug used, especially when patients present early (e.g. <15min from seizure onset) when midazolam is most effective. Indeed, this study did not seek to use ketamine as a sole agent but only as an adjunctive therapy to midazolam.

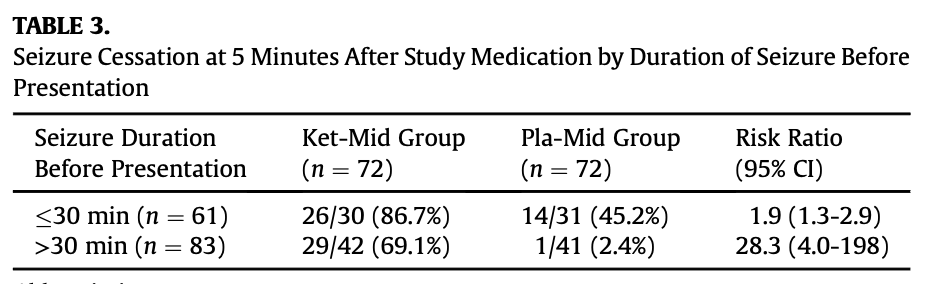

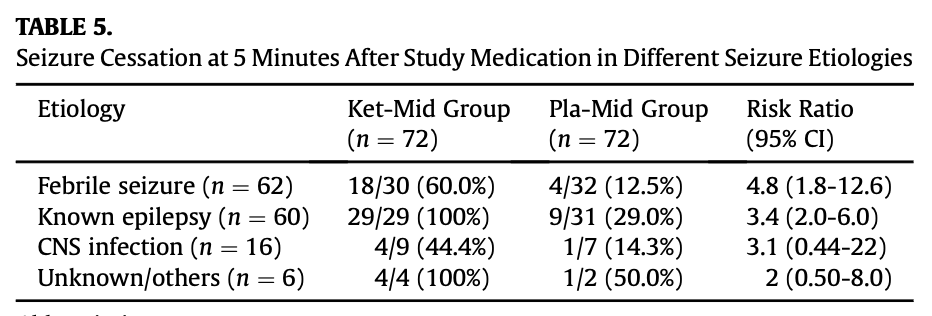

- The big, question is whether to generalise these findings to adults. About 1/3 of the patients in the study were older children between the ages of 5-16y.o and ketamine was at least as effective in this sub-group (see study table 4 below). Also reassuringly, ketamine was similarly effective regardless of whether the presumed cause of seizures was febrile convulsions or epilepsy (see study table 5 below). Finally, on the whole, all of the other primary treatments used in the treatment of status epilepticus are effective in for both children and adults, so there is little reason to suspect ketamine to be an exception. Collectively these findings, together with prior observational data, provide support for likely efficacy in adults. Given the balancing of harms and benefits discussed above using a very safe medication for a condition causing serious permanent neurological disability, I think it would be very reasonable to generalise any measured practice change to include adults while awaiting study replication.

- Conclusion: while awaiting study replication, it would be reasonable to change practice as follows:

- Follow your local Status Epilepticus algorithm as normal. If you lack an easily accessible, robust, evidence-based guideline, here is one that we’ve produced. Seek expert help and guidance if you seek to incorporate the below suggestions.

- Consider using ketamine as an adjuvant therapy in patients:

- Presenting early who have failed to respond to initial appropriately dosed midazolam e.g. 10mg midazolam in adults (as 2 x 5mg doses or 1 x 10mg dose – see midazolam dosing discussion in this guideline) or a dose of 0.15mg/kg in paeds.

- Such patients frequently fail to respond to simply escalating the midazolam doses alone, though this should still be tried as per guidelines either if ketamine fails to immediately resolve the seizure or in combination with ketamine. It is plausible, though unproven, that using ketamine at this stage may reduce the total amount of benzodiazepines required, which in turn may reduce post seizure airway and breathing complications.

- Presenting late, as initial treatment in combination with midazolam (as in this study)

- Presenting early who have failed to respond to initial appropriately dosed midazolam e.g. 10mg midazolam in adults (as 2 x 5mg doses or 1 x 10mg dose – see midazolam dosing discussion in this guideline) or a dose of 0.15mg/kg in paeds.

- Definitely use ketamine in intractable status epilepticus before the use of a general anaesthetic (e.g. propofol) and intubation, unless there are other indications for intubation.

- Note that if ketamine provides benefit, do not otherwise waiver from other important aspects of the algorithm such as the simultaneous or subsequent administration of IV anticonvulsant medications (e.g. levetiracetam/phenytoin/valproate). Additionally, as a new adjuvant treatment, excessive team focus on ketamine should not unnecessarily delay initial dosing of midazolam.

- Please note our disclaimer and cross-check the following with alternative resources and senior clinicians.

- The study used a very large dose (2mg/kg) delivered as an infusion over 2 minutes. I suspect the dose was chosen for research related reasons to maximise the chance of efficacy with a standardised dosing schedule. It is quite possible that lower doses will be efficacious in some patients.

- In the study, the total infusion volume delivered in children was 0.4ml/kg to a maximum of 12ml = 60mg i.e. 5mg/mL dilution. i.e if the child was greater than 30kg, then received the maximum 60mg dose.

- Delivering such an infusion in the real-world would be practically difficult and time consuming in an emergency, when not already set up to do so for research purposes. Ketamine is typically delivered as titrated boluses in common ED practice. While usually incredibly safe, large rapid boluses of ketamine (such as 1-2mg/kg boluses) have been reported to cause apnoea.

- Dilution ratio:

- For familiarity and to reduce the risk of dosing errors, draw up ketamine in the usual dilution ratio used in your ED.

- E.g. In all my EDs we draw up ketamine to 10mg/mL dilution which would result in giving half the volume they gave in the study to achieve the same dose.

- If for some reason your ED draws up ketamine very dilutely, then I would not dilute to a lower concentration than that used in the study (5mkg/mL) or the total volume would exceed that given in the study.

- For familiarity and to reduce the risk of dosing errors, draw up ketamine in the usual dilution ratio used in your ED.

- Total dose to to draw up

- For adults it would be reasonable to just draw up the whole 200mg vial if that’s what you usually would do e.g. we would draw up 200mg in 20mL (note for adults >100kg, you may require more than the standard 200mg vial drawn up either at the start or as needed).

- In children it would likely be safer to draw up 4 x 0.5mg/kg doses in 4 separate syringes (see below) – to follow the study protocol, the maximum combined dose for all 4 syringes should not exceed 4 x 15mg syringes = 60mg in total.

- Dose Delivery

- Then deliver a 0.5mg/kg bolus every 60 seconds – in children that’s just 1 of the 4 pre-drawn syringes while in adults it is simply the appropriate dose-volume from the single drawn up syringe. Ketamine works in 1 arm-brain-time, so you need only 60 seconds to evaluate effect before redosing, and there is only downside in redosing quicker than this – 60 seconds is the “Goldilocks zone”.

- Safety is likely optimised by ceasing administration at the lowest effective dose. So, when seizures terminate it would be reasonable to cease further administration, so the total dose may end up being anywhere from 0.5mg/kg-2mg/kg delivered.

- Examples:

- For a 30kg child draw up 4 syringes of 0.5mg x 30 = 15mg in each syringe. At 10mg/mL (the dilution ratio used in my departments) this would be 1.5mL in each syringe

- Deliver 1 syringe every 60 seconds till either seizure termination or the 4 syringes are delivered, whichever occurs first.

- For an 80kg adult, we would typically draw up 200mg of ketamine in one 20mL syringe (10mg/mL)

- Then deliver 0.5mg x 80 = 40mg = 4mL every 60 seconds till either seizure termination or the total 2mg/kg dose (16mL) is reached, whichever occurs first.

- For a 30kg child draw up 4 syringes of 0.5mg x 30 = 15mg in each syringe. At 10mg/mL (the dilution ratio used in my departments) this would be 1.5mL in each syringe

- Following this rational approach would mean practically easier (titrated boluses instead of infusion) and safer dosing of ketamine is delivered to both prevent apnoea and minimise the overall dose required but still be delivered rapidly. Even if a full 2 mg/kg was required this would occur as 0.5mg/kg doses at time 0, 60s, 120s, 180s, meaning the full dose was delivered in approximately 3 minutes (only 1 minute longer than the 2min infusion duration in the study).